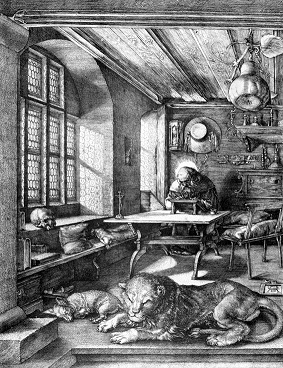

St. Jerome in His Study- Albrecht Dürer. 1514

When first initiated into the lodge as an Entered Apprentice, we state that we desire “Light in Masonry.” At the time, it may not be entirely evident what that light is. However, as we progress through our Masonic life, we learn that Light in Masonry is equivalent to knowledge, and in fact equivalent to certain kinds of knowledge. In the ancient Mystery School traditions, there were considered to be 3 primary types of knowledge, each one of which is exemplified by one of the three degrees of Masonry.

To us, in modern times, we tend to consider knowledge to be knowledge. No matter how you learn something, no matter how you feel you know something, it is all simply “knowledge.” This was not the case for the Ancients. In fact, the Greeks had multiple words that all could be translated as “knowledge,” but meant vastly different things. Those are what I would like to explore in this post. The Greco-Egyptian mystics and initiates into the Mysteries were astutely aware that different knowledge can be imparted in different ways, and that a person can learn different things better in different ways. For example, have you ever tried to learn calculus through meditation? Would you try to learn welding through charity? I feel very certain that it can’t be done. Each type of knowledge has a certain source inherent in it.

Episteme – Knowledge Through Craft – The Entered Apprentice

The first type of knowledge I’d like to explore is episteme (from Greek έπιστὴμη, pronounced eh-pee-STAY-may). This is what I will call, “knowledge through craft.” Episteme is knowledge that is gained through working with your hands, or practicing a craft, a hobby, a trade, etc. Although I do not intend to imply that any of these types of knowledge are lesser or greater than another, this type of knowledge would relate to the 1° – Entered Apprentice. In this first degree, we are taught to rectify our bodies and to improve the soma (from Greek σῶμα, SOH-mah), which is what Gnostic teachings call our physical body – and the anima (from Latin, AH-nee-mah), which is the base aspect of our soul that we share in common with all living creatures. We are taught to use the working tools of an Entered Apprentice to remove the “vices and superfluities” of our lives, in order to purify ourselves. It’s interesting to note that the 1° working tools (specifically the Gavel) are the only ones that we apply in a physical manner to ourselves. Whereas the tools of the 2° and 3° are applied in a more metaphorical manner (“admonishing” us or “reminding” us), the C∴G∴ is used directly to divest ourselves of vices and superfluities. This is yet another allusion to the knowledge of this degree being the kind that can only be gained by doing. It is through this “hands-on” knowledge that we can become more in touch with our physical selves, and with the physical aspect of our soul, in order to purify it.

Mathesis – Knowledge Through Thought – The Fellowcraft

Mathesis (μάθησις, MAH-thay-sis) is probably the closest of these three to our modern idea of knowledge. This is knowledge gained through thought and reason, knowledge such as mathematics (a word that shares a common etymological root with mathesis), science, philosophy, etc. The second degree of Freemasonry, that of Fellowcraft, is intensely concerned with this scientific knowledge. We are taught the seven liberal arts and sciences – some of which admittedly overlap a bit with the next type of knowledge – in order to raise our minds to a higher level. Through mathesis, we are able to improve the aspect of our soul called the psyche (from Greek ψυχή, p’soo-KHAY). The psyche is the part of our being centered in our brain – it is knowledge and reason, an aspect of our being that we do not share with the other creatures of the Earth – an aspect that makes us uniquely human.

Pathesis – Knowledge Through Emotion – The Master Mason

I will admit that, at first glance, “knowledge through emotion” is an odd thing to associate with the Master Mason, but it is the best term I could think of to describe this type of knowledge. Pathesis (from Greek πάθησις, PAH-thay-sis), is perhaps the purest form of knowledge, one that cannot be put into words. This form of knowledge is what the Greco-Egyptian mystery schools were centered around, and what we still focus on today in our Fraternity. As I’ve mused on before, there are certain truths that are so sublime that they cannot be put into words. The symbols of the degrees, the emotions of the degrees, the feelings you feel when you’re going through the degree – these things change you as a person. Perhaps you cannot quite explain how, or maybe even why, but you know deep inside yourself that they have changed you. You know something more about yourself, and in fact even about humanity and the Universe. This equates with the portion of the soul called the pneuma (from Greek πνεῦμα, p’NOO-mah), which is the “spirit” of the body – the portion we share with the Holy Spirit of the Godhead.

Gnosis – Bringing It All Together

I know I mentioned that there are only three types of knowledge that I’d like to explore today, and that is true. But Gnosis (from Greek γνῶσις, g’NOH-sis or NOH-sis) is the umbrella term used to refer to the three collectively. Gnosis as a more specific term, as used by the Gnostics, refers to the divine knowledge that we spend our entire lives searching for. Herein lies a very interesting connection with alchemical teachings. One of the key maxims in alchemy is “solve et coagula” – separate and combine. In practical alchemy, a material must be broken down into its basic parts before it can be purified and brought back together as a more perfect whole. The same aspect applies to us as men and Masons. The three degrees of Masonry teach us to separate our thoughts and, through doing so, to separate the very parts of our soul, in order to purify them on their own so that they may be recombined into a more perfect whole. Our entire lives are to be spent in the purification state – for truly we will not see ourselves brought together into a purified whole until we cross through to that Lodge Eternal. My charge to you, brethren, is to forever improve your craft and your hobbies; forever improve your mind through study; and forever improve your emotions through circumspection and compassion – in doing this, I promise you, you will purify the very essence of your soul.

_________________________________________

Thank you for reading The Laudable Pursuit!

If you enjoyed this piece, please feel free to share it on social media sites and with your Lodge.

For more information on Bro. Ian B. Tuten, Please CLICK HERE:

Also, visit us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheLaudablePursuit

Bibliography:

Baum, Julius. The Mysteries. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1955.

Walker, Benjamin. Gnosticism: its history and influence. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: Aquarian Press, 1983.

Hermes Trismegistus. Corpus Hermeticum. Translated by G. R. S. Mead.

Sickels, Daniel. General Ahiman Rezon. 1968.